Textual history and structure

The epic is traditionally ascribed to Vyasa, who is also a major character in the epic. The first section of the Mahabharata states that it was Ganesha who, at the request of Vyasa, wrote down the text to Vyasa's dictation. Ganesha is said to have agreed to write it only on condition that Vyasa never pause in his recitation. Vyasa agreed, provided Ganesha took the time to understand what was said before writing it down.

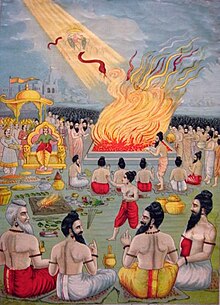

The epic employs the story within a story structure, otherwise known as frametales, popular in many Indian religious and secular works. It is recited to the KingJanamejaya who is the great-grandson of Arjuna, by Vaisampayana, a disciple of Vyasa. The recitation of Vaisampayana to Janamejaya is then recited again by a professional storyteller named Ugrasrava Sauti, many years later, to an assemblage of sages performing the 12 year long sacrifice for King Saunaka Kulapati in theNaimisha forest.

Accretion and redaction

Research on the Mahabharata has put an enormous effort into recognizing and dating various layers within the text. The background to the Mahabharata suggests a time "after the very early Vedic period" and before "the first Indian 'empire' was to rise in the third century B.C.," so "a date not too far removed from the eighth or ninth century B.C."[6] It is generally agreed, however, that "Unlike the Vedas, which have to be preserved letter-perfect, the epic was a popular work whose reciters would inevitably conform to changes in language and style."[6] The earliest surviving components of this dynamic text are believed to be no older than the earliest external references we have to the epic, which may include an allusion in Panini's fourth century BCE grammar (Ashtādhyāyī 4:2:56).[1][6] It is estimated that the Sanskrit text probably reached something of a "final form" by the early Gupta period (about the 4th century CE).[6] Vishnu Sukthankar, editor of the first great critical edition of the Mahabharata, commented: "It is useless to think of reconstructing a fluid text in a literally original shape, on the basis of an archetype and a stemma codicum. What then is possible? Our objective can only be to reconstruct the oldest form of the text which it is possible to reach on the basis of the manuscript material available."[7] That manuscript evidence is somewhat late, given its material composition and the climate of India, but it is very extensive.

The Mahabharata itself (1.1.61) distinguishes a core portion of 24,000 verses, the Bharata proper, as opposed to additional secondary material, while the Ashvalayana Grhyasutra (3.4.4) makes a similar distinction. At least three redactions of the text are commonly recognized: Jaya (Victory) with 8,800 verses attributed to Vyasa, Bharata with 24,000 verses as recited by Vaisampayana, and finally the Mahabharata as recited by Ugrasrava Sauti with over 100,000 verses.[8][9] However, some scholars such as John Brockington, argue that Jaya and Bharata refer to the same text, and ascribe the theory of Jaya with 8,800 verses to a misreading of a verse in Adiparvan (1.1.81).[10] The redaction of this large body of text was carried out after formal principles, emphasizing the numbers 18[11] and 12. The addition of the latest parts may be dated by the absence of the Anushasana-parva and "Virat-parva" from MS Spitzer, the oldest surviving Sanskrit philosophical manuscript dated to Kushan Period (200 CE),[12] that contains among other things a list of the books in the Mahabharata. From this evidence, it is likely that the redaction into 18 books took place in the first century. An alternative division into 20 parvas appears to have co-existed for some time. The division into 100 sub-parvas (mentioned in Mbh. 1.2.70) is older, and most parvas are named after one of their constituent sub-parvas. The Harivamsa consists of the final two of the 100 sub-parvas, and was considered an appendix (khila) to the Mahabharata proper by the redactors of the 18 parvas.[citation needed]

According to what one character says at Mbh. 1.1.50, there were three versions of the epic, beginning with Manu (1.1.27), Astika (1.3, sub-parva 5) or Vasu (1.57), respectively. These versions would correspond to the addition of one and then another 'frame' settings of dialogues. The Vasu version would omit the frame settings and begin with the account of the birth of Vyasa. The astika version would add the sarpasattra andashvamedha material from Brahmanical literature, introduce the name Mahabharata, and identify Vyasa as the work's author. The redactors of these additions were probably Pancharatrin scholars who according to Oberlies (1998) likely retained control over the text until its final redaction. Mention of the Huna in the Bhishma-parva however appears to imply that this parva may have been edited around the 4th century[citation needed].

The Adi-parva includes the snake sacrifice (sarpasattra) of Janamejaya, explaining its motivation, detailing why all snakes in existence were intended to be destroyed, and why in spite of this, there are still snakes in existence. This sarpasattra material was often considered an independent tale added to a version of the Mahabharata by "thematic attraction" (Minkowski 1991), and considered to have a particularly close connection to Vedic (Brahmana) literature. The Panchavimsha Brahmana (at 25.15.3) enumerates the officiant priests of a sarpasattra among whom the names Dhrtarashtra and Janamejaya, two main characters of the Mahabharata's sarpasattra, as well as Takshaka, the name of a snake in the Mahabharata, occur.[13]

The state of the text has been described by some early 20th century Indologists as unstructured and chaotic. Hermann Oldenberg supposed that the original poem must once have carried an immense "tragic force", but dismissed the full text as a "horrible chaos."[14] The judgement of other early 20th century Indologists was even less favourable. Moritz Winternitz (Geschichte der indischen Literatur 1909) considered that "only unpoetical theologists and clumsy scribes" could have lumped the various parts of disparate origin into an unordered whole.

Historical references

See also: Bhagavad gita#Date_and_text

The earliest known references to the Mahabharata and its core Bharata date back to the Ashtadhyayi (sutra 6.2.38) of Pāṇini (fl. 4th century BCE), and in the Ashvalayana Grhyasutra (3.4.4). This may suggest that the core 24,000 verses, known as the Bharata, as well as an early version of the extended Mahabharata, were composed by the 4th century BCE.

The Greek writer Dio Chrysostom (ca. 40-120) reported, "it is said that Homer's poetry is sung even in India, where they have translated it into their own speech and tongue. The result is that...the people of India...are not unacquainted with the sufferings of Priam, the laments and wailings of Andromache and Hecuba, and the valor of both Achilles and Hector: so remarkable has been the spell of one man's poetry!"[15],Despite the passage's evident face-value meaning—that the Iliad had been translated into Sanskrit—some scholars have supposed that the report reflects the existence of a Mahabharata at this date, whose episodes Dio or his sources syncretistically identify with the story of the Iliad. Christian Lassen, in his Indische Alterthumskunde, supposed that the reference is ultimately to Dhritarashtra's sorrows, the laments of Gandhari and Draupadi, and the valor of Arjuna and Duryodhana or Karna.[16] This interpretation, endorsed in such standard references as Albrecht Weber's History of Indian Literature, has often been repeated without specific reference to what Dio's text says.[17]

Several stories within the Mahabharata took on separate identities of their own in Classical Sanskrit literature. For instance, Abhijñānashākuntala by the renowned Sanskrit poet Kālidāsa (ca. 400 CE), believed to have lived in the era of the Gupta dynasty, is based on a story that is the precursor to the Mahabharata. Urubhanga, a Sanskrit play written by Bhāsa who is believed to have lived before Kālidāsa, is based on the slaying of Duryodhana by the splitting of his thighs by Bhima.

The copper-plate inscription of the Maharaja Sharvanatha (533-534 CE) from Khoh (Satna District, Madhya Pradesh) describes the Mahabharata as a "collection of 100,000 verses" (shatasahasri samhita).